Indo-Pakistani War of 1971

| Indo-Pakistani War of 1971 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Indo-Pakistani Wars and Bangladesh Liberation War | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

India |

Pakistan |

||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 500,000 troops | 365,000 troops | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 3,843 killed [1] 9,851 wounded[1] 1 Frigate 1 Naval Plane |

9,000 killed[2] 4,350 wounded 97,368 captured[3] 2 Destroyers[4] 1 Minesweeper[4] 1 Submarine[5][6] 3 Patrol vessels 7 Gunboats |

||||||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

The Indo-Pakistani War of 1971 was a military conflict between India and Pakistan. Indian, Bangladeshi and international sources consider the beginning of the war to be Operation Chengiz Khan, Pakistan's December 3, 1971 pre-emptive strike on 11 Indian airbases.[7][8] Lasting just 13 days it is considered one of the shortest wars in history.[9][10]

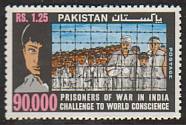

During the course of the war, Indian and Pakistani forces clashed on the eastern and western fronts. The war effectively came to an end after the Eastern Command of the Pakistan Military signed the Instrument of Surrender, the first and perhaps the only public surrender till date [11] [12], on December 16, 1971 following which East Pakistan seceded as the independent state of Bangladesh. Around 97,368 West Pakistanis who were in East Pakistan at the time of its independence, including some 79,700 Pakistan Army soldiers and paramilitary personnel[13] and 12,500 civilians,[13] were taken as prisoners of war by India.

Contents |

Background

The Indo-Pakistani conflict was sparked by the Bangladesh Liberation war, a conflict between the traditionally dominant West Pakistanis and the majority East Pakistanis.[4] The Bangladesh Liberation war ignited after the 1970 Pakistani election, in which the East Pakistani Awami League won 167 of 169 seats in East Pakistan and secured a simple majority in the 313-seat lower house of the Majlis-e-Shoora (Parliament of Pakistan). Awami League leader Sheikh Mujibur Rahman presented the Six Points to the President of Pakistan and claimed the right to form the government. After the leader of the Pakistan Peoples Party, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, refused to yield the premiership of Pakistan to Mujibur, President Yahya Khan called the military, dominated by West Pakistanis to suppress dissent[14][15].

Mass arrests of dissidents began, and attempts were made to disarm East Pakistani soldiers and police. After several days of strikes and non-cooperation movements, the Pakistani military cracked down on Dhaka on the night of 25 March 1971. The Awami League was banished, and many members fled into exile in India. Mujib was arrested on the night of 25–26 March 1971 at about 1:30 a.m. (as per Radio Pakistan’s news on 29 March 1971) and taken to West Pakistan.

On 27 March 1971, Ziaur Rahman, a rebellious major in the Pakistani army, declared the independence of Bangladesh on behalf of Mujibur[16]. In April, exiled Awami League leaders formed a government-in-exile in Baidyanathtala of Meherpur. The East Pakistan Rifles, a paramilitary force, defected to the rebellion. A guerrilla troop of civilians, the Mukti Bahini, was formed to help the Bangladesh Army.

India's involvement in Bangladesh Liberation War

The Pakistan army conducted a widespread genocide against the Bengali population of East Pakistan,[17] aimed in particular at the minority Hindu population,[18][19] leading to approximately 10 million[18][20] people fleeing East Pakistan and taking refuge in the neighboring Indian states.[17][21] The East Pakistan-India border was opened to allow refugees safe shelter in India. The governments of West Bengal, Bihar, Assam, Meghalaya and Tripura established refugee camps along the border. The resulting flood of impoverished East Pakistani refugees placed an intolerable strain on India's already overburdened economy.[19]

General Tikka Khan earned the nickname 'Butcher of Bengal' due to the widespread atrocities he committed.[7] General Niazi commenting on his actions noted 'On the night between 25/26 March 1971 General Tikka struck. Peaceful night was turned into a time of wailing, crying and burning. General Tikka let loose everything at his disposal as if raiding an enemy, not dealing with his own misguided and misled people. The military action was a display of stark cruelty more merciless than the massacres at Bukhara and Baghdad by Chengiz Khan and Halaku Khan... General Tikka... resorted to the killing of civilians and a scorched earth policy. His orders to his troops were: 'I want the land not the people...' Major General Farman had written in his table diary, "Green land of East Pakistan will be painted red". It was painted red by Bengali blood.'[22]

The national Indian government repeatedly appealed to the international community, but failing to elicit any response,[23] Prime Minister Indira Gandhi on 27 March 1971 expressed full support of her government for the independence struggle of the people of East Pakistan. The Indian leadership under Prime Minister Gandhi quickly decided that it was more effective to end the genocide by taking armed action against Pakistan than to simply give refuge to those who made it across to refugee camps.[21] Exiled East Pakistan army officers and members of the Indian Intelligence immediately started using these camps for recruitment and training of Mukti Bahini guerrillas.[24]

India's official engagement with Pakistan

Objective

By November, war seemed inevitable; a massive buildup of Indian forces on the border with East Pakistan had begun. The Indian military waited for winter, when the drier ground would make for easier operations and Himalayan passes would be closed by snow, preventing any Chinese intervention. On 23 November, Yahya Khan declared a state of emergency in all of Pakistan and told his people to prepare for war.[25]

On the evening of 3 December Sunday, at about 5:40 p.m.,[26] the Pakistani Air Force (PAF) launched a pre-emptive strike on eleven airfields in north-western India, including Agra which was 300 miles (480 km) from the border. During this attack the Taj Mahal was camouflaged with a forest of twigs and leaves and draped with burlap because its marble glowed like a white beacon in the moonlight.[27]

This preemptive strike known as Operation Chengiz Khan, was inspired by the success of Israeli Operation Focus in the Arab-Israeli Six Day War. But, unlike the Israeli attack on Arab airbases in 1967 which involved a large number of Israeli planes, Pakistan flew no more than 50 planes to India and failed to inflict the intended damage.[28] As a result, the Indian runways were cratered and rendered non-functional for several hours after the attack.[29]

In an address to the nation on radio that same evening, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi held that the air strikes were a declaration of war against India[30][31] and the Indian Air Force responded with initial air strikes that very night. These air strikes were expanded to massive retaliatory air strikes the next morning and there after.[32]

This marked the official start of the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971. Prime Minister Indira Gandhi ordered the immediate mobilization of troops and launched the full-scale invasion. This involved Indian forces in a massive coordinated air, sea, and land assault. Indian Air Force started flying sorties against Pakistan from midnight and quickly achieved air superiority.[4][27] The main Indian objective on the western front was to prevent Pakistan from entering Indian soil. There was no Indian intention of conducting any major offensive into West Pakistan.[26]

In the western theatre of the war, the Indian Navy, under the command of Vice Admiral Kohli, achieved success by attacking Karachi's port in the code-named Operation Trident[4] on the night of 4–5 December[4], which resulted in the sinking of the Pakistani destroyer PNS Khyber and a minesweeper PNS Muhafiz; PNS Shajehan was badly damaged[4]. This resulted in tactical Indian success: 720 Pakistani sailors were killed or wounded, and Pakistan lost reserve fuel and many commercial ships, thus crippling the Pakistan Navy's further involvement in the conflict. Operation Python[4] followed Operation Trident which was on the night of 8–9 December[4], in which Indian rocket-armed motor torpedo boats attacked the Karachi Roads that resulted in further destruction of reserve fuel tanks, and in the sinking of three Pakistani commercial ships in Karachi Harbour.[4]

In the eastern theatre of the war, the Indian Eastern Naval Command, under Vice Admiral Krishnan, completely isolated East Pakistan by establishing a naval blockade in the Bay of Bengal, trapping the Eastern Pakistani Navy and eight foreign merchant ships in their ports. From 4 December onwards, the aircraft carrier INS Vikrant was deployed in which its Sea Hawk fighter-bombers attacked many coastal towns in East Pakistan including Chittagong and Cox's Bazaar. Pakistan responded by sending the submarine PNS Ghazi to negate the threat.[5] Indian Eastern Naval Command laid a trap to sink the submarine and Indian Navy destroyer INS Rajput sank Pakistani submarine PNS Ghazi through depth charges off Vishakapatnam's coast[33][34] reducing Pakistan's control of Bangladeshi coastline[6] . But on 9 December, the Indian Navy suffered its biggest wartime loss when the Pakistani submarine PNS Hangor sank the frigate INS Khukri in the Arabian Sea resulting in a loss of 18 officers and 176 sailors.[35]

The damage inflicted on the Pakistani Navy stood at 7 gunboats, 1 minesweeper, 1 submarine, 2 destroyers, 3 patrol crafts belonging to the coast guard, 18 cargo, supply and communication vessels, and large scale damage inflicted on the naval base and docks in the coastal town of Karachi. Three merchant navy ships - Anwar Baksh, Pasni and Madhumathi - [36] and ten smaller vessels were captured.[37] Around 1900 personnel were lost, while 1413 servicemen were captured by Indian forces in Dhaka.[38] According to one Pakistan scholar, Tariq Ali, the Pakistan Navy lost a third of its force in the war.[39]

Air operations

After the initial preemptive strike, PAF adopted a defensive stance in response to the Indian retaliation. As the war progressed, the Indian Air Force continued to battle the PAF over conflict zones[40], but the number of sorties flown by the PAF gradually decreased day-by-day.[41] The Indian Air Force flew 4,000 sorties while its counterpart, the PAF offered little in retaliation, partly because of the paucity of non-Bengali technical personnel.[4] This lack of retaliation has also been attributed to the deliberate decision of the PAF High Command to cut its losses as it had already incurred huge losses in the conflict.[42] The PAF also did not intervene during the Indian Navy's raid on Pakistani naval port city of Karachi.

In the east, the small air contingent of Pakistan Air Force No. 14 Sqn was destroyed, putting the Dhaka airfield out of commission and resulting in Indian air superiority in the east.[4]

Ground operations

Pakistan attacked at several places along India's western border with Pakistan, but the Indian army successfully held their positions. The Indian Army quickly responded to the Pakistan Army's movements in the west and made some initial gains, including capturing around 5,500 square miles (14,000 km2) of Pakistan territory (land gained by India in Pakistani Kashmir, Pakistani Punjab and Sindh sectors was later ceded in the Simla Agreement of 1972, as a gesture of goodwill).

On the eastern front, the Indian Army joined forces with the Mukti Bahini to form the Mitro Bahini ("Allied Forces"); Unlike the 1965 war which had emphasized set-piece battles and slow advances, this time the strategy adopted was a swift, three-pronged assault of nine infantry divisions with attached armored units and close air support that rapidly converged on Dhaka, the capital of East Pakistan.

Lieutenant General Jagjit Singh Aurora, who commanded the eighth, twenty-third, and fifty-seventh divisions, led the Indian thrust into East Pakistan. As these forces attacked Pakistani formations, the Indian Air Force rapidly destroyed the small air contingent in East Pakistan and put the Dhaka airfield out of commission. In the meantime, the Indian Navy effectively blockaded East Pakistan.

The Indian campaign employed "blitzkrieg" techniques, exploiting weakness in the enemy's positions and bypassing opposition, and resulted in a swift victory.[43] Faced with insurmountable losses, the Pakistani military capitulated in less than a fortnight. On 16 December, the Pakistani forces stationed in East Pakistan surrendered.

Surrender of Pakistani forces in East Pakistan

The Instrument of Surrender of Pakistani forces stationed in East Pakistan was signed at Ramna Race Course in Dhaka at 16.31 IST on 16 December 1971, by Lieutenant General Jagjit Singh Aurora, General Officer Commanding-in-chief of Eastern Command of the Indian Army and Lieutenant General A. A. K. Niazi, Commander of Pakistani forces in East Pakistan. As Aurora accepted the surrender, the surrounding crowds on the race course began shouting anti-Niazi and anti-Pakistan slogans.[44]

India took approximately 90,000 prisoners of war, including Pakistani soldiers and their East Pakistani civilian supporters. 79,676 prisoners were uniformed personnel, of which 55,692 were Army, 16,354 Paramilitary, 5,296 Police, 1000 Navy and 800 PAF.[45] The remaining prisoners were civilians - either family members of the military personnel or collaborators (razakars). The Hamoodur Rahman Commission report instituted by Pakistan lists the Pakistani POWs as follows:

| Branch | Number of captured Pakistani POWs |

|---|---|

| Army | 54,154 |

| Navy | 1,381 |

| Air Force | 833 |

| Paramilitary including police | 22,000 |

| Civilian personnel | 12,000 |

| Total: | 90,368 |

American and Soviet involvement

The United States supported Pakistan both politically and materially. President Richard Nixon and his Secretary of State Henry Kissinger feared Soviet expansion into South and Southeast Asia.[46] Pakistan was a close ally of the People's Republic of China, with whom Nixon had been negotiating a rapprochement and where he intended to visit in February 1972. Nixon feared that an Indian invasion of West Pakistan would mean total Soviet domination of the region, and that it would seriously undermine the global position of the United States and the regional position of America's new tacit ally, China. In order to demonstrate to China the bona fides of the United States as an ally, and in direct violation of the US Congress-imposed sanctions on Pakistan, Nixon sent military supplies to Pakistan, routing them through Jordan and Iran,[47] while also encouraging China to increase its arms supplies to Pakistan. The Nixon administration also ignored reports it received of the "genocidal" activities of the Pakistani Army in East Pakistan, most notably the Blood telegram. This prompted widespread criticism and condemnation both by Congress and in the international press.[17][48][49]

When Pakistan's defeat in the eastern sector seemed certain, Nixon ordered the USS Enterprise into the Bay of Bengal. The Enterprise arrived on station on 11 December 1971. It has been documented that Nixon even persuaded Iran and Jordan to send their F-86, F-104 and F-5 fighter jets in aid of Pakistan.[50] On 6 December and 13 December, the Soviet Navy dispatched two groups of ships and a submarine, armed with nuclear missiles, from Vladivostok; they trailed U.S. Task Force 74 into the Indian Ocean from 18 December 1971 until 7 January 1972. The Soviets also had a nuclear submarine to help ward off the threat posed by USS Enterprise task force in the Indian Ocean.[51]

The Soviet Union sympathized with the Bangladeshis, and supported the Indian Army and Mukti Bahini during the war, recognizing that the independence of Bangladesh would weaken the position of its rivals—the United States and China. The USSR gave assurances to India that if a confrontation with the United States or China developed, it would take counter-measures. This assurance was enshrined in the Indo-Soviet friendship treaty signed in August 1971.

Aftermath

India

The war stripped Pakistan of more than half of its population and with nearly one-third of its army in captivity, clearly established India's military dominance of the subcontinent.[20] In spite of the magnitude of the victory, India was surprisingly restrained in its reaction. Mostly, Indian leaders seemed pleased by the relative ease with which they had accomplished their goals—the establishment of Bangladesh and the prospect of an early return to their homeland of the 10 million Bengali refugees who were the cause of the war.[20] In announcing the Pakistani surrender, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi declared in the Indian Parliament:

"Dacca is now the free capital of a free country. We hail the people of Bangladesh in their hour of triumph. All nations who value the human spirit will recognize it as a significant milestone in man's quest for liberty."[20]

Pakistan

For Pakistan it was a complete and humiliating defeat,[20] a psychological setback that came from a defeat at the hands of intense rival India.[13] Pakistan lost half its territory, significant portion of its economy and its geo-political role in South Asia.[13] Pakistan feared that the two-nation theory was disproved and that the Islamic ideology had proved insufficient to keep Bengalis part of Pakistan.[13] Also, the Pakistani military suffered further humiliation by having their 90,000 prisoners of war (POWs) released by India only after the negotiation and signing of the Simla Agreement on July 2, 1972. In addition to repatriation of prisoners of war also, the agreeement established an ongoing structure for the negotiated resolution of future conflicts between India and Pakistan (referring to the remaining western provinces that now composed the totality of Pakistan). In signing the agreement, Pakistan also, by implication, recognized the former East Pakistan as the now independent and sovereign state of Bangladesh.

The Pakistani people were not mentally prepared to accept defeat, the state-controlled media in West Pakistan had been projecting imaginary victories.[13] When the surrender in East Pakistan was finally announced, people could not come terms with the magnitude of defeat, spontaneous demonstrations and mass protests erupted on the streets of major cities in West Pakistan. Also, referring to the remaining rump Western Pakistan as simply "Pakistan" added to the effect of the defeat as international acceptance of the secession of the eastern half of the country and its creation as the independent state of Bangladesh developed and was given more credence.[13] The cost of the war for Pakistan in monetary and human resources was very high. Demoralized and finding himself unable to control the situation, General Yahya Khan surrendered power to Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto who was sworn-in on 20 December 1971 as President and as the (first civilian) Chief Martial Law Administrator. A new and smaller western-based Pakistan emerged on 16 December 1971.[52]

The loss of East Pakistan had shattered the prestige of the Pakistani military.[13] Pakistan lost half its navy, a quarter of its air force and a third of its army.[53] The popularized myth that one Muslim had the fighting prowess of five Hindus no longer held any legitimacy.[13] The war also exposed the shortcoming of Pakistan's declared strategic doctrine that the "defence of East Pakistan lay in West Pakistan".[54] Hussain Haqqani, in his book Pakistan: Between Mosque and Military notes,

"Moreover, the army had failed to fulfill its promises of fighting to the last man. The eastern command had laid down arms after losing only 1,300 men in battle. In West Pakistan 1,200 military deaths had accompanied lack luster military performance." [55]

In his book The 1971 Indo-Pak War: A Soldier’s Narrative Pakistani Major General Hakeem Arshad Qureshi a veteran of this conflict noted,

"We must accept the fact that, as a people, we had also contributed to the bifurcation of our own country. It was not a Niazi, or a Yahya, even a Mujib, or a Bhutto, or their key assistants, who alone were the cause of our break-up, but a corrupted system and a flawed social order that our own apathy had allowed to remain in place for years. At the most critical moment in our history we failed to check the limitless ambitions of individuals with dubious antecedents and to thwart their selfish and irresponsible behaviour. It was our collective ‘conduct’ that had provided the enemy an opportunity to dismember us."[56]

Bangladesh

Bangladesh became an independent nation, the world's third most populous Muslim state. Mujibur Rahman was released from a West Pakistani prison, returned to Dhaka on 10 January 1972 and to become first President of Bangladesh and later its Prime Minister.

On the brink of defeat around 14 December, the Pakistani Army, and its local collaborators, systematically killed a large number of Bengali doctors, teachers and intellectuals,[57][58] part of a pogrom against the Hindu minorities who constituted the majority of urban educated intellectuals.[59][60] Young men, especially students, who were seen as possible rebels were also targeted. The extent of casualties in East Pakistan is not known. R.J. Rummel cites estimates ranging from one to three million people killed.[61] Other estimates place the death toll lower, at 300,000. Bangladesh government figures state that Pakistani forces aided by collaborators killed three million people, raped 200,000 women and displaced millions of others.[62] In 2010 Bangladesh government set up a tribunal to prosecute the people involved in alleged war crimes and those who collaborated with Pakistan.[63] According to the Government, the defendants would be charged with Crimes against humanity, genocide, murder, rape and arson.[64]

Hamoodur Rahman Commission

In aftermath of war Pakistan Government constituted the Hamoodur Rahman Commission headed by Justice Hamoodur Rahman in 1971 to investigate the political and military causes for defeat and the Bangladesh atrocities during the war. The commission's report was classified and its publication banned by Bhutto as it put the military in poor light, until some parts of the report surfaced in Indian media in 2000.

When it was declassified, it showed many failings from the strategic to the tactical levels. It confirmed the looting, rapes and the killings by the Pakistan Army and their local agents. It lay the blame squarely on Pakistani generals, accusing them of war crimes and neglect of duty. Though no actions were ever taken on commissions findings, the commission had recommended public trial of Pakistan Army generals.

Simla Agreement

In 1972 the Simla Agreement was signed between India and Pakistan, the treaty ensured that Pakistan recognized the independence of Bangladesh in exchange for the return of the Pakistani POWs. India treated all the POWs in strict accordance with the Geneva Convention, rule 1925[27]. It released more than 90,000 Pakistani PoWs in five months[65]. Further, as a gesture of goodwill, nearly 200 soldiers who were sought for war crimes by Bengalis were also pardoned by India.

The accord also gave back more than 13,000 km² of land that Indian troops had seized in West Pakistan during the war, though India retained a few strategic areas.[66] But some in India felt that the treaty had been too lenient to Bhutto, who had pleaded for leniency, arguing that the fragile democracy in Pakistan would crumble if the accord was perceived as being overly harsh by Pakistanis and that he would be accused of losing Kashmir in addition to the loss of East Pakistan[13].

Long term consequences

- Steve Coll, in his book Ghost Wars, argues that the Pakistan military's experience with India, including Pervez Musharraf's experience in 1971, influenced the Pakistani government to support jihadist groups in Afghanistan even after the Soviets left, because the jihadists were a tool to use against India, including bogging down the Indian Army in Kashmir.[67][68]

- After the war, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto came to power. Pakistan launched Project-706, a secret nuclear weapon development program, to defend itself from India. A vast majority of Pakistani nuclear scientists who were working at the International Atomic Energy Agency and European and American nuclear programs immediately came to Pakistan and joined Project-706.

Important dates

- 7 March 1971: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman declares that, "The current struggle is a struggle for independence", in a public meeting attended by almost a million people in Dhaka.

- 25 March 1971: Pakistani forces start Operation Searchlight, a systematic plan to eliminate any resistance. Thousands of people are killed in student dormitories and police barracks in Dhaka.

- 26 March 1971: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman signed an official declaration of independence and sent it through a radio message on the night of 25 March (the morning of 26 March). Later Major Ziaur Rahman and other Awami League leaders announced the declaration of independence on behalf of Sheikh Mujib from Kalurghat Radio Station, Chittagong. The message is relayed to the world by Indian radio stations.

- 17 April 1971: Exiled leaders of Awami League form a provisional government.

- 3 December 1971: War between India and Pakistan officially begins when West Pakistan launches a series of preemptive air strikes on Indian airfields.

- 6 December 1971: East Pakistan is recognized as Bangladesh by India.

- 14 December 1971: Systematic elimination of Bengali intellectuals is started by Pakistani Army and local collaborators.[59]

- 16 December 1971: Lieutenant-General A. A. K. Niazi, supreme commander of Pakistani Army in [East Pakistan, surrenders to the Allied Forces (Mitro Bahini) represented by Lieutenant General Jagjit Singh Arora of Indian Army at the surrender. Bangladesh gains victory

- 12 January 1972: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman comes to power

Military awards

For bravery, a number of soldiers and officers on both sides were awarded the highest military award of respective countries. Following is a list of the recipients of the Indian award Param Vir Chakra, Bangladeshi award Bir Sreshtho and the Pakistani award Nishan-E-Haider:

India

Recipients of the Param Vir Chakra:

- Lance Naik Albert Ekka (Posthumously)

- Flying Officer Nirmal Jit Singh Sekhon (Posthumously)

- Major Hoshiar Singh

- Second Lieutenant Arun Khetarpal (Posthumously)

Bangladesh

Recipients of the Bir Sreshtho

- Captain Mohiuddin Jahangir (Posthumously)

- Lance Naik Munshi Abdur Rouf (Posthumously)

- Sepoy Hamidur Rahman (Posthumously)

- Sepoy Mostafa Kamal (Posthumously)

- ERA Mohammad Ruhul Amin (Posthumously)

- Flight Lieutenant Matiur Rahman (Posthumously)

- Lance Naik Nur Mohammad Sheikh (Posthumously)

Pakistan

Recipients of the Nishan-E-Haider:

- Major Muhammad Akram (Posthumously)

- Pilot Officer Rashid Minhas (Posthumously)

- Major Shabbir Sharif (Posthumously)

- Sowar Muhammad Hussain (Posthumously)

- Lance Naik Muhammad Mahfuz (Posthumously)

Dramatization

- Films

- Border, a 1997 Bollywood war film directed by J.P.Dutta. This movie is an adaptation from real life events that happened at the Battle of Longewala fought in Rajasthan (Western Theatre) during the 1971 Indo-Pak war. Border at the Internet Movie Database

- Hindustan Ki Kasam, a 1973 Bollywood war film directed by Chetan Anand. The aircraft in the film are all authentic aircraft used in the 1971 war against Pakistan. These include MiG-21s, Gnats, Hunters and Su-7s. Some of these aircraft were also flown by war veterans such as Samar Bikram Shah (2 kills) and Manbir Singh. Hindustan Ki Kasam at the Internet Movie Database

- 1971 - Prisoners of War, a 2007 Bollywood war film directed by Sagar Brothers. Set against the backdrop of a prisoners' camp in Pakistan, follows six Indian prisoners awaiting release after their capture in the 1971 India-Pakistan war.

See also

- Indo-Pakistani War of 1965

- Post-World War II air-to-air combat losses

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Official Government of India Statement giving numbers of KIA, Parliament of India Website

- ↑ Leonard, Thomas. Encyclopedia of the developing world, Volume 1. Taylor & Francis, 2006. ISBN 0415976626, 9780415976626.

- ↑ Quantification of Losses Suffered

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 "Indo-Pakistani War of 1971". Global Security. http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/war/indo-pak_1971.htm. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "The Sinking of the Ghazi". Bharat Rakshak Monitor, 4(2). http://www.bharat-rakshak.com/MONITOR/ISSUE4-2/harry.html. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Operations in the Bay of Bengal: The Loss of PNS/M Ghazi". PakDef. http://www.pakdef.info/pakmilitary/navy/1971navalwar/lossofghazi.htm. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Gen. Tikka Khan, 87; 'Butcher of Bengal' Led Pakistani Army". Los Angeles Times. 30 March 2002. http://articles.latimes.com/2002/mar/30/local/me-passings30.1. Retrieved 11 April 2010.

- ↑ Cohen, Stephen (2004). The Idea of Pakistan. Brookings Institution Press. pp. 382. ISBN 0815715021. http://books.google.com/?id=-78yjVybQfkC&lpg=PP1&dq=Google%20books%20The%20idea%20of%20Pakistan%20%2F%20Stephen%20Philip%20Cohen&pg=PA8#v=onepage&q.

- ↑ The World: India: Easy Victory, Uneasy Peace, Time (magazine), 1971-12-27

- ↑ World’s shortest war lasted for only 45 minutes, Pravda, 2007-03-10

- ↑ [1],

- ↑ [2]

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 13.7 13.8 13.9 Haqqani, Hussain (2005). Pakistan: Between Mosque and Military. United Book Press. ISBN 0-87003-214-3, 0-87003-223-2. http://books.google.com/?id=nYppZ_dEjdIC&lpg=PP1&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q=., Chapter 3, pp 87.

- ↑ Sarmila Bose Anatomy of Violence: Analysis of Civil War in East Pakistan in 1971: Military Action: Operation Searchlight Economic and Political Weekly Special Articles, 8 October 2005

- ↑ Salik, Siddiq, "Witness To Surrender.", ISBN 9-840-51373-7, pp63, p228-9.

- ↑ Annex M (Oxford University Press, 2002 ISBN 0-19-579778-7).

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 "The U.S.: A Policy in Shambles". Time Magazine, 20 December 1971. 20 December 1971. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,878970,00.html. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 U.S. Consulate (Dacca) Cable, Sitrep: Army Terror Campaign Continues in Dacca; Evidence Military Faces Some Difficulties Elsewhere, 31 March 1971, Confidential, 3 pp.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "East Pakistan: Even the Skies Weep". Time Magazine, 25 October 1971. 25 October 1971. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,877316,00.html. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 "India: Easy Victory, Uneasy Peace". Time Magazine, 27 December 1971. 27 December 1971. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,905593,00.html. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 "Indo-Pakistani Wars". MSN Encarta. Archived from the original on 2009-10-31. http://www.webcitation.org/5kwrHv6ph. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ↑ Haqqani, Hussain (2005). Pakistan: between mosque and the military. Carnegie Endowment. pp. 74. ISBN 0870032143. http://books.google.com/?id=nYppZ_dEjdIC&lpg=PP1&dq=Google%20books%20The%20idea%20of%20Pakistan%20%2F%20Stephen%20Philip%20Cohen&pg=PA74#v=onepage&q. Retrieved 2010-04-11.

- ↑ "The four Indo-Pak wars". Kashmirlive, 14 September 2006. http://www.kashmirlive.com/latest/The-four-IndoPak-wars/73887.html. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ↑ "I had to find troops for Dhaka". Rediff News, 14 December 2006. http://im.rediff.com/news/2006/dec/14jacob.htm. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ↑ "Indo-Pakistani War of 1971". http://www.warchat.org/history-asia/indo-pakistani-war-of-1971.html. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 "War is Delcared". http://www.subcontinent.com/1971war/declared.html. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 "Bangladesh: Out of War, a Nation Is Born". Time Magazine, 20 December 1971. 20 December 1971. http://www.time.com/time/printout/0,8816,878969,00.html. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ↑ "Trying to catch the Indian Air Force napping, Yahya Khan, launched a Pakistani version of Israel's 1967 air blitz in hopes that one rapid attack would cripple India's far superior air power. But India was alert, Pakistani pilots were inept, and Yahya's strategy of scattering his thin air force over a dozen air fields was a bust!", p.34, Newsweek, December 20, 1971

- ↑ "PAF Begins War in the West : 3 December". Institute of Defence Studies. http://www.pakdef.info/pakmilitary/airforce/1971war/warinwest.html. Retrieved 2008-07-04.

- ↑ "India and Pakistan: Over the Edge". Time Magazine, 13 December 1971. 13 December 1971. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,910155-2,00.html. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ↑ "1971: Pakistan intensifies air raids on India". BBC News. 3 December 1971. http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/december/3/newsid_2519000/2519133.stm. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ↑ "Indian Air Force. Squadron 5, Tuskers". Global Security. http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/india/sqn-5.htm. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ↑ http://www.hindu.com/mp/2006/12/02/stories/2006120202090100.htm

- ↑ http://www.rediff.com/news/2007/jan/22inter.htm

- ↑ "Trident, Grandslam and Python: Attacks on Karachi". Bharat Rakshak. http://www.bharat-rakshak.com/NAVY/History/1971War/44-Attacks-On-Karachi.html. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ↑ Utilisation of Pakistan merchant ships seized during the 1971 war

- ↑ "Damage Assesment - 1971 Indo-Pak Naval War" (PDF). B. Harry. http://www.orbat.com/site/cimh/navy/kills(1971)-2.pdf. Retrieved June 20, 2010.

- ↑ "Military Losses in the 1971 Indo-Pakistani War". Venik. http://www.aeronautics.ru/archive/vif2_project/indo_pak_war_1971.htm. Retrieved May 30, 2005.

- ↑ Tariq Ali (1983). Can Pakistan Survive? The Death of a State. Penguin Books Ltd. ISBN 0-14-022401-7.

- ↑ Jon Lake, Air Power Analysis : Indian Airpower, World Air Power Journal, Volume 12

- ↑ Group Captain M. Kaiser Tufail, "Great Battles of the Pakistan Airforce" and "Pakistan Air Force Combat Heritage" (pafcombat) et al, Feroze sons, ISBN 9690018922

- ↑ "Indo-Pakistani conflict". Library of Congress Country Studies. http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?frd/cstdy:@field(DOCID+in0189). Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ↑ Paret, Peter (1986). Makers of Modern Strategy: From Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198200978. http://books.google.com/?id=F0N59g93EBYC&lpg=PA189&dq=ISBN%200198200978&pg=PA189#v=onepage&q=., pp802

- ↑ Kuldip Nayar. "Of betrayal and bungling". The Indian Express, 3 February 1998. http://www.indianexpress.com/res/web/pIe/ie/daily/19980203/03450744.html. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ↑ "Huge bag of prisoners in our hands". Bharat Rakshak. http://www.bharat-rakshak.com/1971/Dec16/index.html. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ↑ "Foreign Relations, 1969-1976, Volume E-7, Documents on South Asia, 1969-1972". US State Department. http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ho/frus/nixon/e7/48213.htm. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ↑ Stephen R Shalom. "The Men Behind Yahya in the Indo-Pak War of 1971". http://coat.ncf.ca/our_magazine/links/issue47/articles/a07.htm. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ↑ Hanhimäki, Jussi (2004). The flawed architect: Henry Kissinger and American foreign policy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195172218. http://books.google.com/?id=pPjrpGUe7CEC

- ↑ "The Nixon Administration's South Asia policy... is beyond redemption.", wrote former USAID director John Lewis. John P. Lewis (9 Dec 1971). ""Mr. Nixon and South Asia"". New York Times. http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F30915FB3D5A137A93CBA91789D95F458785F9.

- ↑ Burne, Lester H.. Chronological History of U.S. Foreign Relations: 1932-1988. Routledge, 2003. ISBN 041593916X, 9780415939164.

- ↑ "Cold war games". Bharat Rakshak. http://www.bharat-rakshak.com/NAVY/History/1971War/Games.html. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ↑ Abdus Sattar Ghazali. "Islamic Pakistan, The Second Martial Law". http://ghazali.net/book1/chapter_5.htm. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ↑ Ali, Tariq (1997). Can Pakistan Survive? The Death of a State. Verso Books. ISBN 0860919498, 9780860919490. http://books.google.com/?id=moJPPgAACAAJ&dq=Can+Pakistan+Survive%3F.

- ↑ "Prince, Soldier, Statesman - Sahabzada Yaqub Khan". Defence Journal. http://www.defencejournal.com/2000/oct/yaqub.htm. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ↑ Dr. Ahmad Faruqui. "General Niazi's Failure in High Command". http://www.ghazali.net/book8/Chapter_5/body_chapter_5.html. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ↑ EXCERPTS: We never learn, Dawn (newspaper), 2002-12-15

- ↑ "125 Slain in Dacca Area, Believed Elite of Bengal". New York Times (New York, NY, USA): p. 1. 19 December 1971. http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F50C13F83C5E127A93CBA81789D95F458785F9. Retrieved 2008-01-04. "At least 125 persons, believed to be physicians, professors, writers and teachers, were found murdered today in a field outside Dacca. All the victims' hands were tied behind their backs and they had been bayoneted, garroted or shot. These victims were among an estimated 300 Bengali intellectuals who had been seized by West Pakistani soldiers and locally recruited supporters."

- ↑ Murshid, Tazeen M. (2 December 1997). "State, nation, identity: The quest for legitimacy in Bangladesh". South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, (Routledge) 20 (2): 1–34. doi:10.1080/00856409708723294. ISSN 14790270.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Khan, Muazzam Hussain (2003), "Killing of Intellectuals", Banglapedia, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh

- ↑ Shaiduzzaman. "Martyred intellectuals: martyred history". The Daily New Age, Bangladesh. http://www.newagebd.com/2005/dec/15/murdered/murdered.html. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ↑ Rummel, Rudolph J., "Statistics of Democide: Genocide and Mass Murder Since 1900", ISBN 3-8258-4010-7, Chapter 8, table 8.1

- ↑ Bangladesh sets up war crimes court, Al Jazeera English, 2010-03-26

- ↑ Bangladesh sets up 1971 war crimes tribunal, BBC, 2010-03-25

- ↑ Bangladesh to Hold Trials for 1971 War Crimes, Voice of America, 2010-03-26

- ↑ 54 "Indian PoWs of 1971 war still in Pakistan". Daily Times. http://www.dailytimes.com.pk/default.asp?page=story_19-1-2005_pg7_28 54. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ↑ "The Simla Agreement 1972". Story of Pakistan. http://www.storyofpakistan.com/articletext.asp?artid=A109&Pg=6. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ↑ Coll, Steve (2005). Ghost Wars. The Penguin Press. ISBN 1-59420-007-6. http://books.google.com/?id=ToYxFL5wmBIC&lpg=PP1&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q=. pg 221, 475.

- ↑ Kreisler interview with Coll "Conversations with history", 2005 Mar 25, UC Berkeley Institute of International Studies

- "The Rediff Interview/Lt Gen A A Khan Niazi". Rediff. 2 February 2004. http://www.rediff.com/../news/2004/feb/02inter1.htm.

Further reading

- Haqqani, Hussain (2005). Pakistan: Between Mosque and Military. United Book Press. ISBN 0-87003-214-3, 0-87003-223-2. http://books.google.com/?id=nYppZ_dEjdIC&lpg=PP1&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q=.

- Ayub, Muhammad (2005). An army, its role and rule: a history of the Pakistan Army from Independence to Kargil, 1967-1999. RoseDog Books. ISBN 0805995943, 9780805995947. http://books.google.com/?id=B2saAAAACAAJ.

- Palit, D K (1972). The Lightning Campaign: The Indo-Pakistan War 1971. Compton Press Ltd. ISBN 0-900193-10-7. http://books.google.com/?id=rPmTAAAACAAJ.

- Saigal, J R (2000). Pakistan Splits: The Birth of Bangladesh. Manas Publications. ISBN 817049124X, 9788170491248. http://books.google.com/?id=gUfaAAAACAAJ.

- Hanhimäki, Jussi M. (2004). The Flawed Architect: Henry Kissinger and American Foreign Policy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195172213, 978-0195172218. http://books.google.com/?id=3wolOABSg_YC&lpg=PP1&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q=.

- Niazi, General A. A. K. (1999). Betrayal of East Pakistan. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195792750, 9780195792751. http://books.google.com/?id=nYppZ_dEjdIC&lpg=PP1&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q=.

External links

- Video of General Niazi Surrendering

- A complete coverage of the war from the Indian perspective

- An Atlas of the 1971 India - Pakistan War: The Creation of Bangladesh by John H. Gill

- Actual conversation from the then US President Nixon and Henry Kissinger during the 1971 War - US Department of State's Official archive.

- Indian Army: Major Operations

- Pakistan: Partition and Military Succession USA Archives

- Pakistan intensifies air raid on India BBC

- A day by day account of the war as seen in a virtual newspaper.

- The Tilt: The U.S. and the South Asian Crisis of 1971.

- 16 December 1971: any lessons learned? By Ayaz Amir - Pakistan's Dawn (newspaper)

- India-Pakistan 1971 War as covered by TIME

- Indian Air Force Combat Kills in the 1971 war (unofficial), Centre for Indian Military History

- Op Cactus Lilly: 19 Infantry Division in 1971, a personal recall by Lt Col Balwant Singh Sahore

- All for a bottle of Scotch, a personal recall of Major (later Major General) C K Karumbaya, SM, the battle for Magura

- TIME Magazine article from 20 December 1971 describing the War

- TIME Magazine article from 20 December 1971 critical of the US policy during this war

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||